Disappearances in the Zaporizhzhia Region, 24 February to 18 June 2022

This is the first in a series of reports by the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group (KHPG), analysing information about international crimes allegedly committed in Ukraine since 24 February 2022. They are a contribution to the Tribunal for Putin (T4P) global initiative.

According to Article 2 of the “International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance” (to which Ukraine acceded in June 2015) enforced disappearance is considered to be

“the arrest, detention, abduction or any other form of deprivation of liberty by agents of the State or by persons or groups of persons acting with the authorization, support or acquiescence of the State, followed by a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty or by concealment of the fate or whereabouts of the disappeared person, which place such a person outside the protection of the law”.

Under international law, an enforced disappearance is a crime, and if the practice of enforced disappearances is widespread or systematic it is considered, a Crime against Humanity. Article 2.1 of the Convention states that “No exceptional circumstances, whether state of war or threat of war, internal political instability or other State of Emergency, can justify enforced disappearance.”

During the previous Russian-Ukrainian war from 2014 to 2018 the KHPG recorded 4,649 cases of individuals going missing, mostly during fighting in eastern Ukraine. Among the missing individuals were 3,135 men, 645 women and 239 children; the gender of 630 individuals was not defined due to lack of information. As of 30 July 2018, 3,484 of those individuals had been found; the fate of 1,165 remains unknown. The following information is contained in the KHPG database: 983 civilians and 843 members of legal armed formations disappeared in 2014; 361 civilians and 216 military were recorded as missing in 2015; and 178 civilians and 19 military were listed as missing in 2016. In the next three years — 2017, 2018 and the first half of 2019 — we documented and registered in our database the disappearance of 40 civilians and 22 military personnel.

621 of these cases can be classified as enforced disappearances. This means the victims were deprived of the protection of the law after being detained and they could not contact their relatives. At the same time, they were subjected to various actions that can be classified as international crimes: murder, torture, degrading treatment, and unlawful imprisonment.

From the first days of Russia’s all-out war against Ukraine, its armed forces resorted to disappearances, including a great many enforced disappearances. As of 23 June, this year the database of the T4P Initiative contained information about 1,625 victims of disappearances: 800 in the Kharkiv Region, 399 in the Kherson Region, 236 in the Luhansk Region, 136 in the Zaporizhzhia Region, and 54 victims in other Regions.

|

Identity |

Number |

% of total |

|

Former members of the ATO / JFO Operation], |

17 |

13 |

|

Deputies of Regional Assemblies |

26 |

19 |

|

Civil activists, volunteers, active participants |

21 |

15 |

|

Journalists |

8 |

6 |

|

Medical workers |

2 |

1 |

|

Priests |

5 |

4 |

|

Ordinary citizens |

49 |

36 |

|

Teachers, lecturers, etc. |

7 |

5 |

|

Children |

1 |

1 |

|

TOTAL |

111 |

100 |

Table 1. Identity of missing and disappeared in Zaporizhzhia Region

According to a preliminary classification, 510 of these cases fell into the category of enforced disappearances, distributed as follows: 77 case in the Kharkiv Region, 268 in the Kherson Region, 26 in the Luhansk Region, 111 in the Zaporizhzhia Region, and 28 in other Regions. During the first 120 days of all-out war, in other words, the number of enforced disappearances almost equalled the total of all that occurred during the eight years of the previous conflict, according to the data we have collected.

The numerous cases documented since 24 February 2022 of the enforced disappearances or kidnapping of civilians, point to violation of Article 34 [Hostages] (IV) of the Geneva Convention “relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War” (12 August 1949) and Article 75 [Fundamental Guarantees] of the Additional Protocol to the Geneva Conventions relating to “the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol 1, 8 June 1977)”. When a certain critical number of enforced disappearances is reached, they qualify collectively as a Crime against Humanity under Article 7 (1)(і) of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.

Under Ukrainian law, such acts qualify either as “unlawful deprivation of liberty or kidnapping” (Article 146, Ukrainian Criminal Code) or “enforced disappearance” (Article 146-1 of Ukraine’s Criminal Code).

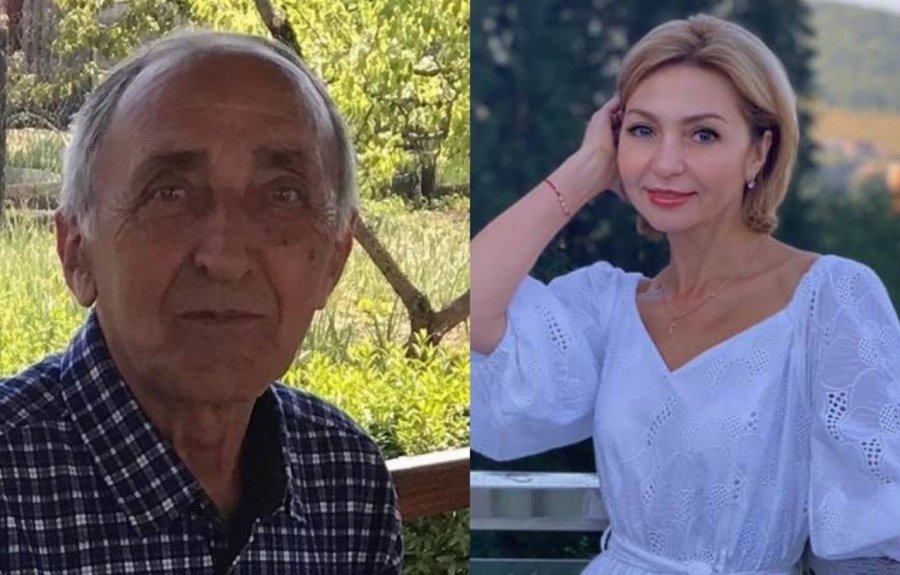

Let us consider disappearances in the Zaporizhzhia Region (Table 1). They have mainly occurred in its temporarily occupied territories. Among the categories of people who disappeared the majority (68 or 59%) were ordinary citizens. They were not working for the media, and there is no information about them. It is proving impossible to determine their fate. Their occupations are unknown, and it remains unclear what category we can put them in.

Since the beginning of the invasion, the occupying forces of the Russian Federation have systematically kidnapped deputies and local government representatives in order to quickly gain control over Ukrainian territory and put pressure on the occupied communities.

The arrest and detention of journalists, volunteers, public activists, lawyers, and active participants in pro-Ukrainian rallies has formed part of the “hunt for dissidents”, aimed at quickly destroying the backbone of society in the temporarily occupied territories.

Human rights defender and journalist P. has described these forms of cruelty:

“I was waiting for my turn, wondering what will happen to me, if ordinary people are being subjected to such treatment. During their search, the Russians found a recording in my phone, ’I’d rather die than live under those Russian arseholes’ (I didn’t make it).

“The Russians didn’t like the recording and got angry. I was taken to the fourth floor where they played the recording again and again and punched me in the stomach. Then they gave me a great ‘history’ lesson. Kievan Rus is part of the Russian Empire, they said and, ranting senselessly, they called Ukrainians fascists, nationalists and said they had been shelling the Donbas for eight years. They wouldn’t believe I didn’t make it myself. The invaders blindfolded me and started discussing what to do with me: they suggested dropping me from the fourth floor. They brought me to a room with broken windows, kicked my legs from under me, holding onto my [shirt] collar with one hand.”

The number of documented cases grows with each passing day, we should add, and the frequency of kidnappings is much higher.

|

Category |

Number |

% of total |

|

held in places of detention (1): |

34 |

25 |

|

held in places of detention (2): |

6 |

4 |

|

Information currently lacking |

95 |

70 |

|

Killed |

1 |

1 |

|

TOTAL |

136 |

100 |

Table 2. Duration of disappearance and / or captivity

Civilians who have disappeared can provisionally be divided into several categories (Table 2) according to how long they’ve been missing.

The overwhelming majority of those kidnapped and subsequently released said they had been subjected to psychological and physical violence.

From the data obtained, it can be concluded that the vast majority of people do not get in touch after being abducted: their relatives and friends are unable to get information about their whereabouts or health; they cannot find out the conditions in which they are being held or the reason for their arrest and detention. Information about the detained is not provided to relatives, and this complicates the search for kidnapped individuals.

A quarter of recorded disappearances (Table 2) indicate periods of detentions that lasted less than two weeks. During that time, allegedly, the occupiers carried out their plans concerning specific individuals, and decided whether to release them or continue holding them in the places of detention.

There is also information about cases where individuals are detained for ransom. Such cases of kidnapping of men have been recorded in the urban centres of the Zaporizhzhia Region: in its second largest city Melitopol (2017 pop: 154,839) and in Tokmak (2013 pop: 32,996). The invaders reacted similarly to all applications by locals about their relatives: “Come in person, such issues are not resolved over the phone,” they were told. When they arrived, relatives were given a “price”. According to the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU), the price of a “return to normal life” depended on the financial resources of the family and ranged from $10,000 (USD) to 30,000.

Individuals were detained in a variety of circumstances. These could be divided (Table 3) into several groups. Over a third of the detained individuals for whom we have records were kidnapped in unknown circumstances.

|

Location and circumstances |

Number |

% of total |

|

Home or summer cottage |

42 |

31 |

|

Workplace |

19 |

14 |

|

During rallies |

4 |

3 |

|

At a checkpoint |

12 |

9 |

|

In the open air |

6 |

4 |

|

Unknown |

53 |

39 |

|

TOTAL |

136 |

100 |

Table 3. Where and in what conditions kidnappings are taking place

It is extremely difficult to track the fate of such people: there are no witnesses and a lack of information concerning the probable reasons for their detention. During such periods of captivity people seem to disappear and for a prolonged period (up to a month, perhaps) their relatives have no information as to their location and state of health.

The wife of M., a detained man:

“My husband was just working, helping people, going to work every day, and resolving important problems faced by the residents of the city. He was doing everything he could to keep the city in order and services running, I know he would never agree to cooperate with the occupiers. Since March, I have had no information where he is or how he is — he simply disappeared.”

There are documented cases of outright lies by representatives of the occupying forces regarding an individual’s location. According to witnesses (people who were arrested or detained with that individual), he/she was in a certain place of detention, but the occupation authorities sent an official response that such an individual was not there. This is psychological abuse, pure and simple, of relatives trying to locate a kidnapped member of their family. Unrecognized detention of any individual is a total violation of guarantees of that person’s liberty and personal integrity (ECtHR Judgment, “Kurt vs. Turkey”, 25 May 1998, 15/1997/799/1002)

The mother of M., a detained individual:

“I am outraged, I don’t know what to do. I’ve heard that my son is in Crimea, but today I received a message from the ‘Department of the Federal Penitentiary Service of the Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol’ stating that my son is not and was never there. Why are they hiding the information?”

A substantial proportion of kidnapped individuals (Table 3) were seized in their own homes. During our documentation of such cases, we found that such arrests are complex in nature: typically, they are combined with searches, intimidation of the family, destruction of property and seizure of valuables and equipment.

Arrests at the workplace were accompanied by searches, seizure of documents and intimidation of colleagues. During open-air arrests, according to cases we documented, the arrest was usually accompanied by beating and violence on the part of the occupying authorities.

At checkpoints they usually arrested volunteers who were helping people to move and ordinary citizens who were trying to leave the temporarily occupied territories. P., a journalist and human rights defender (quoted earlier), describes his arrest as follows:

“When we returned in search of a new route there were ‘orcs’ at the checkpoints. They started shouting, forced me to leave the car and threatened to shoot us. The Russians, it turned out, thought we were spies from Ukrainian territory although we hadn’t even got there yet.

“We were told to pull over. We obeyed. Two soldiers stood nearby, holding grenades. ‘If anyone moves or lowers their arms,’ they said, ‘we’ll toss a grenade under the car.’ They checked our documents and they realized we weren’t spies. But they said that we had too many belongings and they would have to carry out a long search, therefore we had to go with them.”

Arrests during rallies were recorded in several cases, mostly of the organizers and active participants. Unfortunately, it was not possible to follow up the mass arrest of the protesters.

There is no information about the existence of “filtration camps” in the temporarily occupied territories of the Zaporizhzhia Region.

According to Oleksandr Starukh, head of the Zaporizhzhia Regional Military Administration, there are reports of 340 confirmed abductions in the Region. We have therefore documented 40% of cases of the number of officially registered disappearances.

In forthcoming reports, we shall analyse disappearances in the Kharkiv, Kherson and Luhansk Regions and throughout Ukraine in general.

Translation, Vitaly Konkin and John Crowfoot