War Against Nature

The announced “big offensive” by the Russians in 2025 continues to this day, stretching from the Sumy region to Zaporizhzhia and even Kherson. The usual tactic of the Russians throughout all the years of the war is the total destruction of everything that stands in the way of their offensive actions.

In addition to villages, towns, and cities, nature also suffers from shelling and fires. In 2022 alone, more than 60 protected natural areas, reserves, national nature parks, and protected zones were affected by the war. In 2025, the scale of destruction continued to increase.

Journalist and human rights activist Serhii Okunev analyzed several of the most egregious cases and found out how the 2025 offensive is destroying not only cities but also Ukrainian nature.

“Forest of Wonders”. The Serebryansʹkyy and Kremins’kyy forests are almost destroyed

In the fall of 2022, the Ukrainian armed forces achieved large-scale successes in the east: in a matter of days, vast territories in the Kharkiv and Donetsk regions were liberated. In particular, Ukrainian defenders recaptured a significant area at the junction of the Luhansk and Donetsk regions. The new front line began to run through the Kreminsk’yy Forests National Nature Park.

The “Kreminsk’yy Forests” stretched over 7269 hectares and were home to 127 species of rare animals and 94 species of rare plants. Unique 250-year-old oaks also grew on the national park’s territory. The “Serebryansk’yy Forest” botanical reserve was also part of the nature park.

However, the military almost immediately began calling this picturesque area the “Forest of Wonders.” Unfortunately, this was not so much due to the beautiful landscapes and nature as to the incredible danger that prevailed in the forest after 2022. “It’s a forest of wonders: you go in with legs — you come out without,” the soldiers defending this area joked.

As early as the end of 2022 and into 2023, Russian troops actively tried to regain lost positions, but truly fierce battles in the forests of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions began in 2024. Large-scale fires accompanied prolonged fighting in the forests. If in 2023 the State Emergency Service still had the opportunity to extinguish fires that arose after massive shelling, then, over time, as drones developed and the overall danger increased, this task fell entirely on service members’ shoulders.

In the summer of 2025, the section of the front in the Kreminsk’yy and Serebryansk’yy forests became one of those areas where the occupiers tried to consolidate their gains. Constant shelling, bombing of the forest with guided aerial bombs and drones forced the Ukrainian defenders to almost completely abandon the forests. There were fewer fires, but only because there was virtually nothing left to burn.

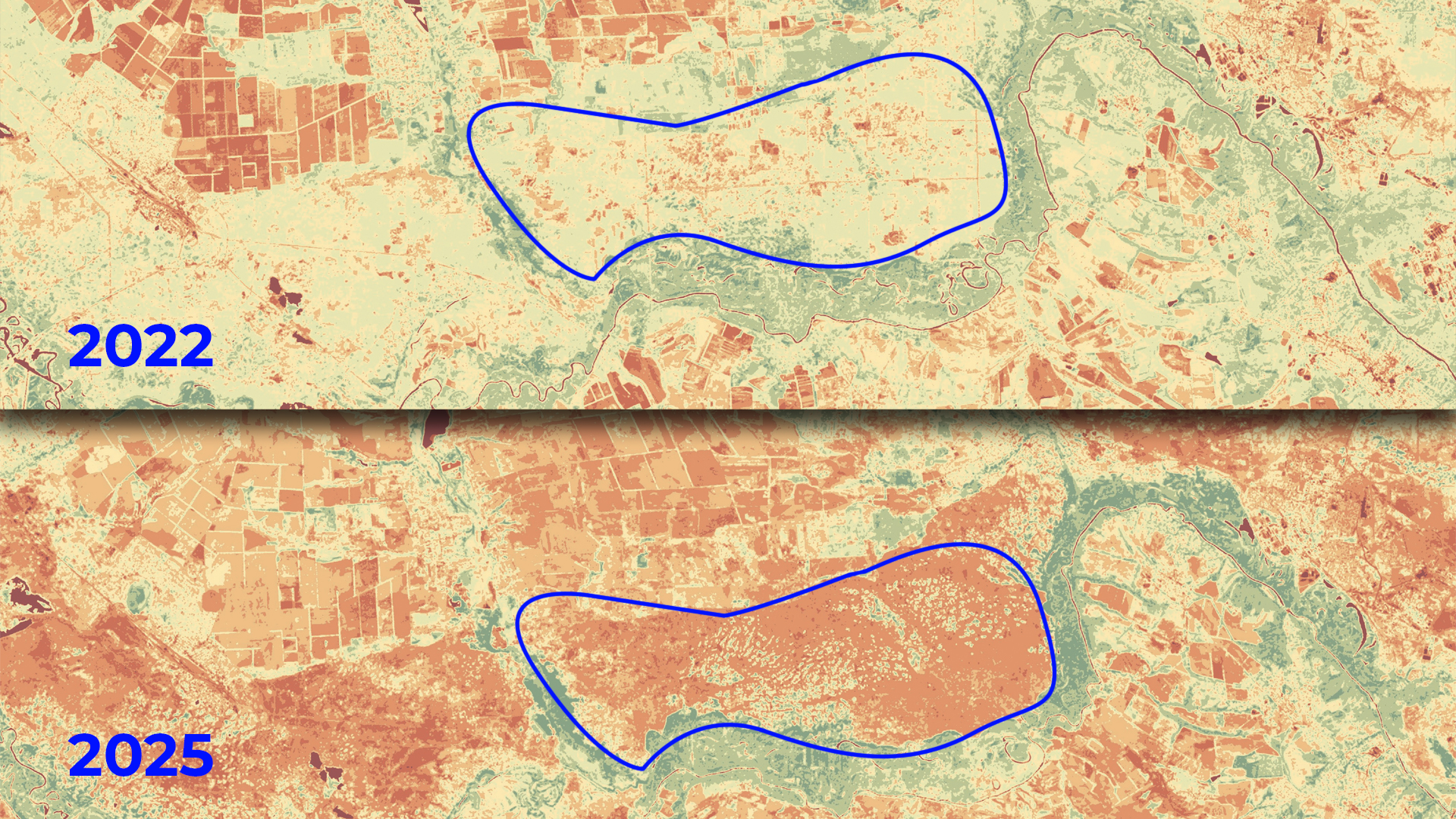

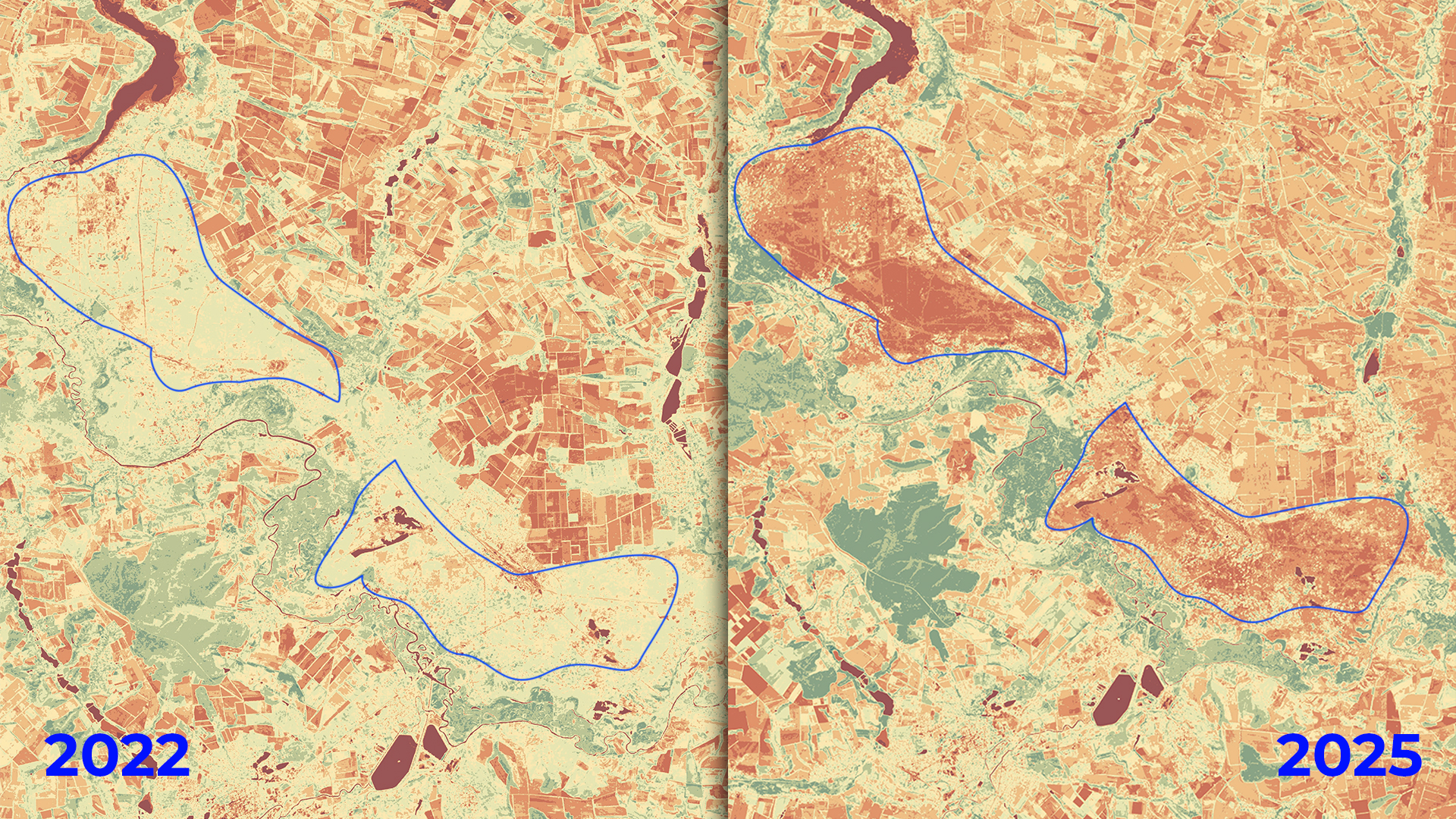

I managed to gain access to NASA satellites that detect changes in vegetation and the Earth’s surface. The peculiarity of these satellites is that they do not simply “show a picture,” but also collect data in 11 spectral channels, including the visible, near-infrared, and far-infrared ranges, as well as thermal channels. This allows for the analysis of changes in forests not simply “by eye,” but through specialized calculations and indicators.

“Donetsk Switzerland” is in flames. Shelling destroys the “Holy Mountains”

Not far from the Kreminna forests is another National Nature Park — “Holy Mountains”. The park was home to 943 plant species, 48 of which are listed in the Red Book of Ukraine. Also, 256 animal species lived in the “Holy Mountains”; 50 of them are listed in the Red Book of Ukraine.

The fauna includes 43 species of mammals, 194 species of birds, 10 species of reptiles, 9 species of amphibians, and 40 species of fish. Before the full-scale invasion, the “Holy Mountains” were jokingly called “Donetsk Switzerland”.

Of the total area of the “Holy Mountains” national nature park, the Russians destroyed about 80%. The chalky slopes, unique to Europe, are disfigured. There were numerous forest fires, and parts of the forest are contaminated with explosive objects.

Satellite images, as before, show critical changes. The area near the city of Svyatohirsk suffered significant damage, as did the areas near Lyman and Raigorodok.

In 2025, after a long lull, the front line near Lyman and Svyatohirsk was reactivated by the Russian occupiers’ advance. Even now, the enemy is actively striking both the cities themselves and the surrounding forests, including the territory of the “Holy Mountains”. In October, OSINT projects reported on individual enemy groups directly on the outskirts of Lyman, indicating an advance of more than 10 kilometers in a short period.

A field of wild orchids and Russian weapons. Kinburn Spit was transformed into a Russian military training ground

The Kinburn Spit is a sandy place located in the Mykolaiv region, which partially separates the Black Sea from the Dnieper estuary. This area regularly ranked among the “top” most beautiful places in Ukraine and in all of Europe. The spit’s territory includes several protected areas, in particular the “Biloberezhzhia Sviatoslava” National Nature Park and the “Kinburn Spit” Regional Landscape Park.

A total of 465 plant species have been found in the park territories, 6 of which are listed in the European Red List, and 9 in the Red Book of Ukraine. It was here that the largest field of wild orchids in Europe was located. And the main “calling card” of the spit was pink pelicans, which are often associated with the national park in the Odesa region, but “Biloberezhzhia Svyatoslava” is also one of the favorite migration places for these birds. The Kinburn Peninsula, the spit, and the nature reserves were occupied in the first days of the war, during the Russian breakthrough in the Kherson region. Control over the peninsula and the spit allowed the Russians to block part of Ukraine’s maritime communication. In addition, in 2022-2023, the occupiers turned the area into a military training ground, from which they shelled the city of Ochakiv.

In early June 2023, the spit was partially flooded as a result of the destruction of the Kakhovka hydroelectric power plant by Russian occupation forces. It is still impossible to assess the damage to the nature reserves, animals, and plants due to the lack of independent experts’ access.

Since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, 426 fires have been recorded on the territory of the Kinburn Spit, affecting more than 9,739 hectares of particularly valuable land, according to the management of the nature park in March 2025.